Self-predicting integer sequences

I will go into quite some mathematical detail in this post. I have tried my best to make the advanced math entirely optional to read. If you are intimidated by the proofs or simply not interested, don’t worry about skimming over them or skipping them entirely. The proofs are meant to give a convincing argument and may not be rigorous.

Whenever I meet up with a certain good friend of mine, we usually have some kind of mathematical microfixation that we like to explore. Around two years ago, we were looking into the properties of some number sequences. Number sequences are an ordered list of numbers, denoted for example \(A_n\). The subscript refers to the \(n\)th element that appears in the sequence. In this post, I will talk about our efforts on a specific integer sequence we found that refers directly to itself. It turned out to take us along more mathematical concepts than I had imagined.

Self-referential sequences

On a late train ride back home, I was trying to think of interesting ideas for integer sequences. Integer sequences are number sequences in which each element is an integer. I enjoyed the idea of creating a sequence that somehow describes itself. Such a sequence is called self-referential. My first thought was to make a sequence that, at each position \(n\), gives the amount of times the number \(n\) appears in the sequence. However, I realized that constructing such a sequence would cause issues soon enough. The problem is that large numbers will take up more space than available. For instance, if the value at a large index \(N\) is another large number \(M\), then the number \(N\) has to appear in a total of \(M\) positions in the sequence. As a result, the numbers corresponding to these positions need to appear \(N\) times themselves! This already occupies \(N \cdot M\) places in the sequence, which is far more than the amount of available places up to position \(N\). For an infinite sequence we can get away with pushing numbers further and further ahead, which will indeed lead to a valid sequence called the Golomb sequence. Moreover, I realized I had previously encountered a similar idea, regarding self-describing numbers instead of sequences. The challenge is to find all the autobiographical numbers, in which the consecutive digits of the number describe the amounts of \(0\)s, \(1\)s, \(2\)s and so forth, up to \(9\)s. An example is the number \(1210\), which contains one \(0\), two \(1\)s, one \(2\) and no \(3\)s.

There are exactly seven autobiographical numbers. Can you find a pattern to construct them? What does this say about the first digit of an infinite autobiographical sequence?

My second idea proved to be more unique: is there an integer sequence that describes at position \(n\) in how many steps we encounter the number \(n\)? We could call this a self-predicting sequence, since it “predicts” when we will see a given number. A couple of ambiguities arise here: can we repeat numbers? Can the sequence refer to a certain number in any position, or does it need to point to the very next occurence of that number? I will address and make suitable choices for these questions while we build the sequence from the ground up.

Constructing the sequence

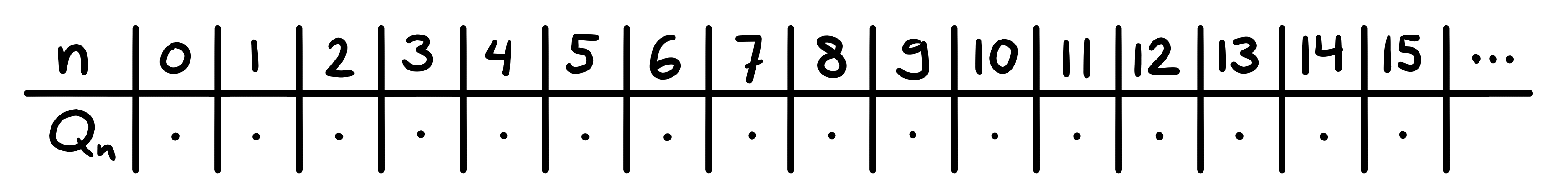

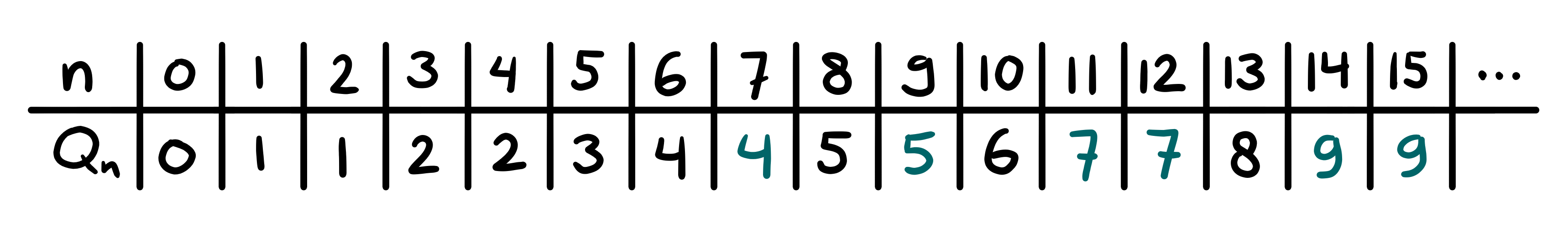

Let’s start with an empty table:

This table will contain the first sixteen elements of our self-predicting sequence. The top row shows the position \(n\) and the bottom row shows the corresponding element in the sequence, which I will call \(Q_n\).

As a start, we can consider \(Q_0\). This number should describe after how many steps we see a \(0\) in the sequence. Let’s think about what happens when a \(0\) appears in the sequence: if at position \(n\) we see \(Q_n = 0\), it tells us that after zero steps we should see the number \(n\). But taking zero steps means we stay at the same position! We cannot have both a \(0\) and an \(n\) in the same position, unless the \(n\) in question is \(0\) itself. This forces \(Q_0\) to be \(0\); any other number would require a \(0\) to appear later on the sequence, which leads to a contradiction.

Now that \(Q_0\) is in place, what could \(Q_1\) be? It surely cannot be a \(0\), as we stated just now. Let’s try \(Q_1 = 1\). In one step, we should then encounter a \(1\), so \(Q_2 = 1\). This in turn tells us that in one step, we should see the number \(2\), so \(Q_3 = 2\). Placing a single number seemingly escalates into a whole list of numbers we can fill in. I will call these number progressions a chain, as each number inside it is linked to the number that initiates it:

An interesting pattern emerges, which some may recognize as the Fibonacci sequence, commonly denoted as \(F_n\). The Fibonacci sequence has the property that each term is the sum of the two numbers prior to it: \(F_n = F_{n-1} + F_{n-2}\) for \(n \geq 2\). It begins with the numbers \(0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, \cdots\).

To see why we encounter these numbers in our self-predicting sequence \(Q_n\), it might help to look at its own defining relation. \(Q_n\) tells us after how many steps we will see an \(n\) in the sequence. In other words, at position \(n + Q_n\), the sequence shows the number \(n\) itself. By the same reasoning, we will encounter the number \(n + Q_n\) at position \((n + Q_n) + n\). Notice that we keep adding the last two numbers to arrive at the new position. This follows the exact same principle as the Fibonacci sequence! Since we put \(Q_1 = 1\), we start out exactly like the original Fibonacci terms \(1, 1, 2, 3, \cdots\) and cause the rest of the chain to unroll.

Time for me to address the first ambiguity, then. Placing a \(1\) at \(Q_1\) already leads to two consecutive \(1\)s to show up in our sequence. If we really want to avoid repeating numbers, we would have to start with a higher number, only to encounter a \(1\) later on. For now, we will allow for repeating numbers. As we will see, repetition of numbers leads to a nicely increasing sequence, rather than one that looks more like an unstable rollercoaster.

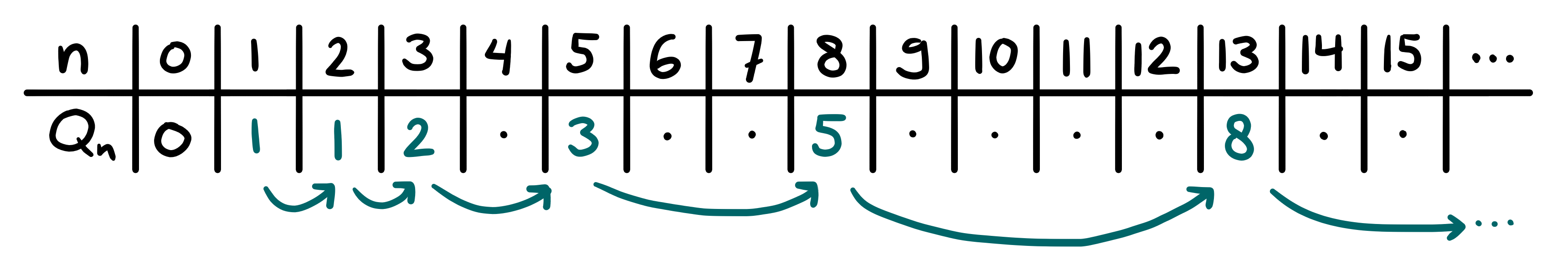

The next blank entry in the table is \(n = 4\). Of course, we cannot fill in any number that points us to a position that is already occupied by another number. This means we are not allowed to enter a \(1\) or a \(4\), because the positions \(n = 5\) and \(n = 8\) are already filled in. However, the numbers \(2\) and \(3\) seem valid. We will enter the smallest number: a \(2\). It’s not a surprise that we again uncover a whole Fibonacci-esque chain of terms:

So far, so good. However, can we be sure that the two Fibonacci chains never overlap? After all, our table only extends up to \(n = 15\), so we can’t see what happens further down the sequence. Perhaps the chains collide somewhere thousands of steps ahead! Luckily, we can prove that they stay out of one another’s ways, under one important condition.

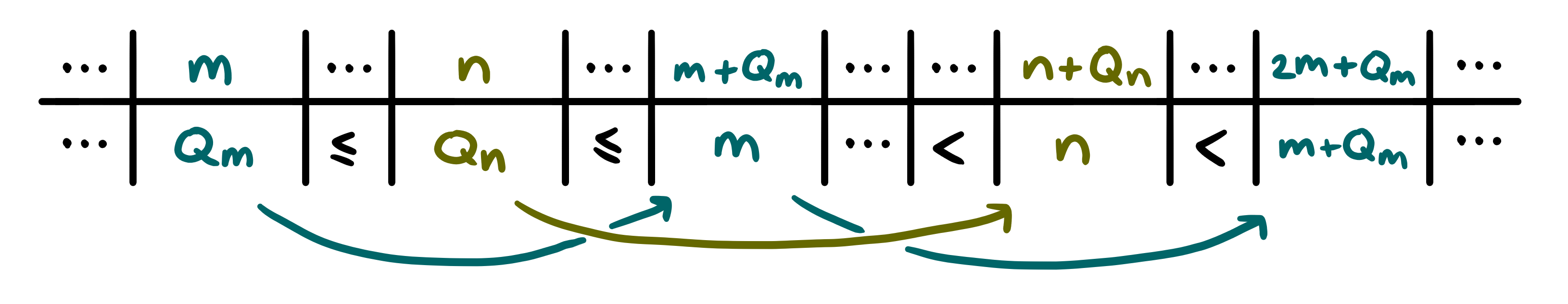

Proof: No overlap between chains

Let's consider a position \(n\) that lies between some \(m\) and the next term of its chain \(m + Q_m\): $$ \begin{equation} m < n < m + Q_m. \end{equation} $$ If we choose for \(Q_n\) a number such that \(Q_m \leq Q_n \leq m\), then the next terms in the two chains are found by adding these inequalities: $$ \begin{equation} m+Q_m < n+Q_n < (m+Q_m) + m, \end{equation} $$ which tells us that the position of the next term of the \(n\)-chain falls neatly between those of the \(m\)-chain. This is shown in the figure below.

We end up in a similar situation as what we started with; the new term in the \(n\)-chain lies somewhere between two terms of the \(m\)-chain, and their corresponding values are strictly increasing. Therefore, the following term of the \(n\)-chain will again fall between the next terms of the \(m\)-chain: $$ \begin{equation} (m+Q_m) + m < (n+Q_n) + n < \left((m+Q_m) + m\right) + (m + Q_m). \end{equation} $$ This pattern repeats indefinitely, which shows that the chains will never collide. Note that \(n\) and \(m\) can be arbitrary numbers appearing anywhere in any (but not the same) chain. As long as \(Q_m \leq Q_n \leq m\), we can be sure that there is no overlap. In most cases, the two direct neighbors of \(n\) will belong to two different chains. To satisfy the requirement above for both neighbor-chains simultaneously, \(Q_n\) is forced to either lie between its adjacent integers or to equal one of them. In other words, any element \(Q_n\) of our self-predicting sequence satisfies (for \(n \geq 1\)): $$ \begin{equation} Q_{n-1} \leq Q_n \leq Q_{n+1}. \end{equation} $$ While this rule is not necessary to build our self-predicting sequence, it is a safe and simple method to avoid any contradictions. It also makes the sequence monotonically increasing, which means the terms only grow or stay the same, but never decrease. We already applied this rule for \(n = 4\), where we set the term \(Q_4 = 2\) equal to its lower neighbor \(Q_3 = 2\). Following the reasoning above, the resulting chains will not coincide anywhere.

We now understand how our sequence behaves and have one rule at hand to avoid any overlap: the value of \(Q_n\) should lie between its neighbors or equal one of them. The rest of the table becomes a lot more straightforward to fill in. \(Q_7\) is bounded by its neighboring terms, so we can choose either a \(4\) or a \(5\). This is where I’ll bring up the second ambiguity: if we pick a \(5\), then \(Q_5\) no longer points to the very next occurence of a \(5\) in the sequence. We will take this as another restriction and only allow the sequence to refer to the very next appearance of a number. When we encounter a blank space, we therefore enter a number that is strictly smaller than any number already filled in further down the sequence. In fact, we can choose to always enter the lowest available number, which is \(Q_n = Q_{n-1}\). Thus, our only option is to set \(Q_7 = 4\). With this extra rule, we can complete our self-predicting sequence:

And there we go! We have constructed a sequence that predicts itself, by only following some simple rules. Although the method is straightforward, producing the sequence up to a large position can take quite some time and effort. Can we do better than this?

From sequence to formula

Like true mathematicians in possession of a brand new integer sequence, we can now start to wonder whether there exists a simple formula for \(Q_n\) in terms of \(n\). Where would we begin? Remember that we have already encountered an interesting property of the sequence: each number we entered, escalated into an elaborate chain of numbers. The Fibonacci-like nature of these chains makes the ratio \(\frac{n}{Q_n}\) of our sequence surprisingly predictable, as we will discover. The Fibonacci sequence itself appeared when we kept adding the previous two terms of a chain to arrive at the next position. The ratio between two consecutive terms in the Fibonacci sequence \(F_n\) and \(F_{n-1}\) approaches the golden ratio \(\varphi\) in the limit where \(n\) grows to infinity. This constant equals \(\frac{1 + \sqrt{5}}{2} \approx 1.6180339887\cdots\). We can use this together with our self-predicting property to show that \(\frac{n}{Q_n}\) also converts to \(\varphi\).

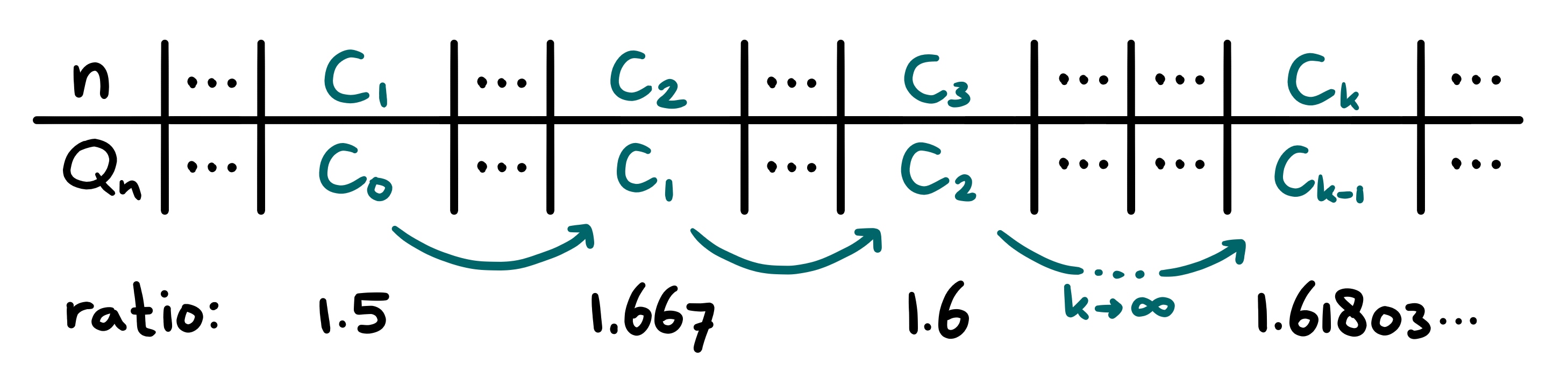

Proof: \(\frac{n}{Q_n}\) approaches the golden ratio

Let's consider some \(Q_n\) in our sequence at index \(n\), which will create a chain of which we will call the elements \(C_k\). We use \(k\) as our index, because \(n\) currently tells us what numbers initiate the chain: \(C_0 = Q_n\) and \(C_1 = n\). The next element of the chain will then be \(C_{k} = C_{k-1} + C_{k-2}\) for \(k>2\), just like the Fibonacci sequence. We will find that the \(k\)-th term of our chain can be written as $$ \begin{equation} C_k = F_{k-1} Q_n + F_k n. \end{equation} $$ We can write: $$ \begin{equation} \lim_{n\,\rightarrow\,\infty} \frac{F_n}{F_{n-1}} = \varphi. \end{equation} $$ The ratio of two successive elements of our chain \(C_k\) can then be reduced as follows: $$ \begin{align} \lim_{k\,\rightarrow\,\infty} \frac{C_k}{C_{k-1}} &= \lim_{k\,\rightarrow\,\infty} \frac{F_{k-1}Q_n + F_k n}{F_{k-2}Q_n + F_{k-1}n},\\ &= \lim_{k\,\rightarrow\,\infty} \frac{Q_n + \frac{F_k}{F_{k-1}} n}{\frac{F_{k-2}}{F_{k-1}}Q_n + n},\\ &= \lim_{k\,\rightarrow\,\infty} \frac{F_{k-1}}{F_{k-2}} \left( \frac{Q_n + \frac{F_k}{F_{k-1}} n}{Q_n + \frac{F_{k-1}}{F_{k-2}}n} \right). \end{align} $$ In the limit where \(k\) grows to infinity, the ratios \(\frac{F_k}{F_{k-1}}\) and \(\frac{F_{k-1}}{F_{k-2}}\) will both approach the golden ratio \(\varphi\), so we end up with $$ \begin{align} \lim_{k\,\rightarrow\,\infty} \frac{C_k}{C_{k-1}} &= \varphi \left( \frac{Q_n + \varphi n}{Q_n + \varphi n} \right),\\ &= \varphi. \end{align} $$ Aha! So no matter where we start in our self-predicting sequence, the ratio between successive terms in the resulting chain will always converge to \(\varphi\), exactly like in the Fibonacci sequence. Of course, our chains also still have the self-predicting property, so \(C_{k-1}\) refers to position \(C_k\) in the sequence, where we will encounter the number \(C_{k-1}\). The ratio \(\frac{C_k}{Q_{C_{k}}} = \frac{C_k}{C_{k-1}}\) between the index and the corresponding value therefore approaches \(\varphi\). The figure below shows what this looks like in our table:

If an index \(m\) is the first to not yet have been occupied by a previous chain, then at least it has to directly follow up on a number \(C_{k-1}\) that does appear in a certain chain. Our rule requires us to set \(Q_m\) equal to its lower neighbor, so \(Q_m = C_{k-1}\). The ratio \(\frac{m}{Q_m}\) will then converge as well: $$ \begin{equation} \lim_{m\,\rightarrow\,\infty} \frac{m}{Q_m} = \lim_{k\,\rightarrow\,\infty} \frac{C_{k} + 1}{C_{k-1}} = \lim_{k\,\rightarrow\,\infty} \frac{C_{k}}{C_{k-1}} = \varphi. \end{equation} $$ Thus, the ratios in our entire self-predicting sequence approach \(\varphi\).

We went on a long tangent to arrive at a simple result: when we take \(n\) large enough, \(\frac{n}{Q_n} \approx \varphi\). Switching this expression around a little gives us our desired relation between \(Q_n\) and \(n\):

\[\begin{equation} Q_n \approx \frac{n}{\varphi}. \end{equation}\]Unfortunately, the two sides of this equation cannot be exactly equal, since we require \(Q_n\) to be an integer and \(\varphi\) is irrational. Clearly, we will need to do some rounding. Let’s dust off an old reliable math tool.

Fiddling with floor functions

What if we simply round \(\frac{n}{\varphi}\) to the nearest integer? We can denote this as follows:

\[\begin{equation} \left\lfloor \frac{n}{\varphi}+\frac{1}{2} \right\rfloor, \end{equation}\]where \(\left\lfloor x \right\rfloor\) is the floor function, which rounds \(x\) down to an integer. A few examples of the floor function are \(\left\lfloor 3.14 \right\rfloor = 3\) and \(\left\lfloor 9.81 \right\rfloor = 9\). If \(x\) is already an integer, then the function will simply return \(x\) itself: \(\left\lfloor 2 \right\rfloor = 2\). Note how we construct a function that rounds up or down to the nearest integer by first adding \(\frac{1}{2}\) to our number. For the given examples, we get \(\left\lfloor 3.14 + \frac{1}{2} \right\rfloor = 3\) but \(\left\lfloor 9.81 + \frac{1}{2} \right\rfloor = 10\).

This rounding function has a certain bias on numbers that lie halfway between two integers. What is this bias and why does it not matter for our sequence?

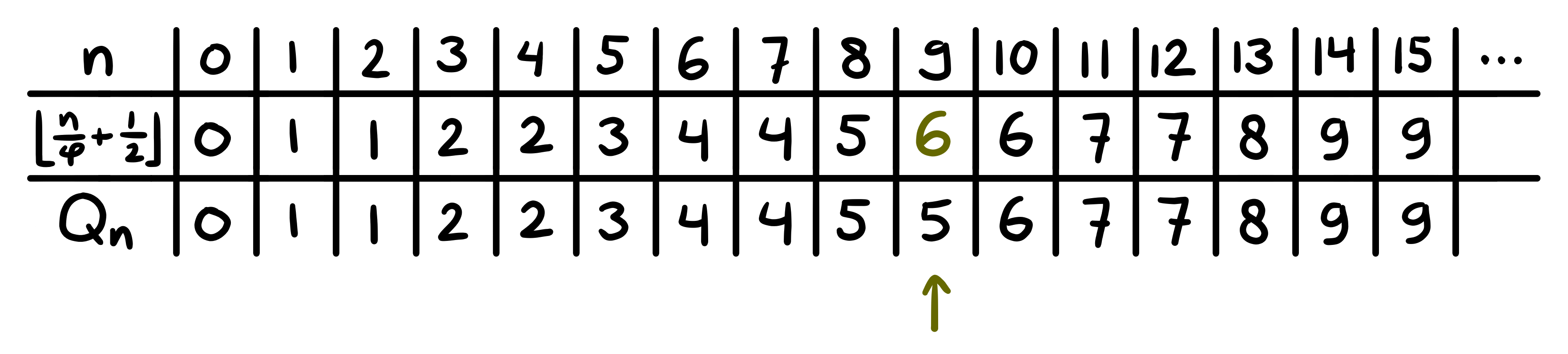

The table corresponding to this straightforward rounding function is shown below, along with the table we constructed before.

This looks a lot like what we were aiming for! The sequence has an entry in The On-Line Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences (OEIS) with index A101803. However, this sequence is not exactly the same as our \(Q_n\). Within the first sixteen terms, only \(Q_9\) is rounded in the wrong direction. It still points to a \(9\), but not to the very next \(9\) in the sequence. Maybe we can obtain the sequence we want by nudging the term \(\frac{1}{2}\) that we added inside the floor function, which I will call the rounding bias. It makes sense to only consider values between \(0\) and \(1\) for the bias, so we can generalize the bias as \(\frac{1}{b}\) with the bias parameter \(b\) ranging from \(1\) to infinity. For the case \(\frac{1}{b} < \frac{1}{2}\), the function will round down more often than it rounds up. Similarly, if \(\frac{1}{b} > \frac{1}{2}\), it rounds up more. With a general bias, our function looks like

\[\begin{equation} Q_{n} = \left\lfloor \frac{n}{\varphi}+\frac{1}{b} \right\rfloor. \end{equation}\]Fascinatingly, there is a range of values for \(b\) for which the sequence predicts itself! Let’s prove it.

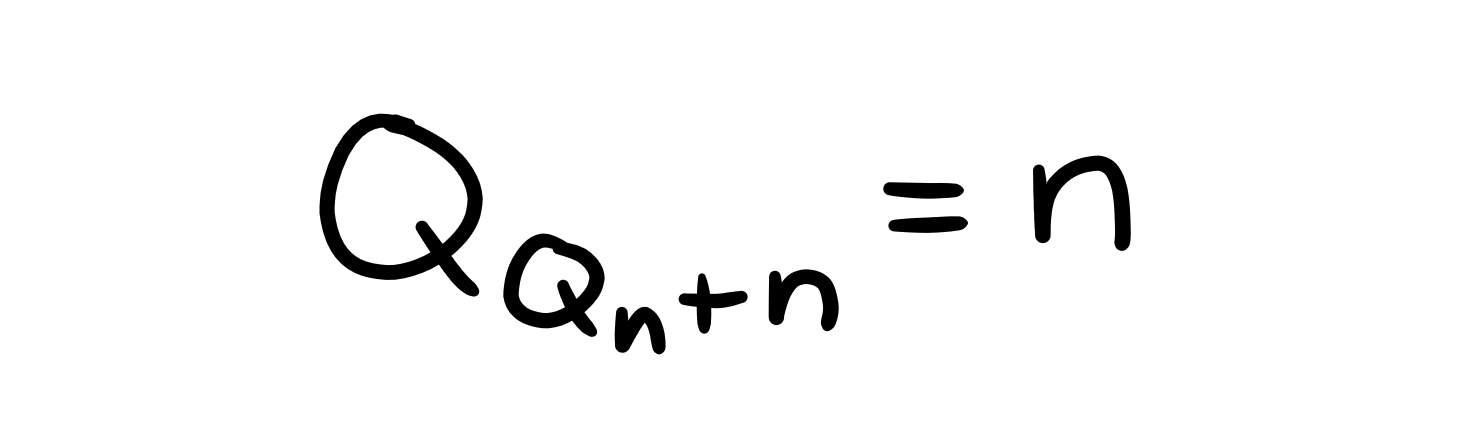

Proof: Range of the bias parameter

We start with the general formula above and rewrite it by applying an interesting property of the golden ratio: \( \frac{1}{\varphi} = \varphi - 1 \). This gives us $$ \begin{equation} Q_{n} = \left\lfloor \frac{n}{\varphi}+\frac{1}{b} \right\rfloor = \left\lfloor n\left( \varphi - 1 \right) + \frac{1}{b} \right\rfloor. \end{equation} $$ Now, what exactly does our self-predicting property tell us about the relation between \(Q_n\) and \(n\)? The element in the sequence at a position \(Q_n\) steps away from position \(n\) is equal to \(n\). Our sequence is therefore described by the recurrence relation $$ \begin{equation} Q_{Q_n+n} = n. \end{equation} $$ Given this recurrece relation and the formula for \(Q_n\) above, we simply substitute the \(n\) in the formula for \(Q_n + n\), and replace \(Q_n\) by its formula again: $$ \begin{align} Q_{Q_n + n} &= \left\lfloor \frac{ Q_n + n}{\varphi} + \frac{1}{b} \right\rfloor,\\ &= \left\lfloor \frac{ \left\lfloor n \left( \varphi - 1 \right) + \frac{1}{b} \right\rfloor + n}{\varphi} + \frac{1}{b} \right\rfloor,\\ &= \left\lfloor \frac{ \left\lfloor n \varphi + \frac{1}{b} \right\rfloor}{\varphi} + \frac{1}{b} \right\rfloor. \end{align} $$ In the last step, we pull the \(n\) into the floor function, which is allowed because \(n\) is an integer. The result looks messy; we now have a nested floor function! However, we know from the recurrence relation that this expression should equal \(n\) in the end, so that is what should restrict the values of \(b\).Let's first inspect the inner floor function a little more closely. In general, if we take the floor of some \( x + \frac{1}{b}\), the result is bounded by $$ \begin{equation} x - 1 + \frac{1}{b} < \left\lfloor x + \frac{1}{b} \right\rfloor \leq x + \frac{1}{b}. \end{equation} $$ The lower bound can be approached when \(x + \frac{1}{b}\) happens to fall ever so slightly below an integer, while the upper bound is reached when it exactly equals an integer. Replacing \(x\) by \(n\varphi\) reveals the boundaries of the inner floor function in our formula: $$ \begin{equation} n\varphi - 1 + \frac{1}{b} < \left\lfloor n\varphi + \frac{1}{b} \right\rfloor \leq n\varphi + \frac{1}{b}. \end{equation} $$ Since \(n\varphi\) is irrational for \(n > 0\), the actual output of this floor function might get arbitrarily close to these boundaries. But remember that we want our formula to equal \(n\) for any \(n\) we enter in the floor function! Otherwise, our self-predicting characteristic fails. We can fix our function between the two boundaries: $$ \begin{equation} \left\lfloor \frac{ n \varphi - 1 + \frac{1}{b}}{\varphi} + \frac{1}{b} \right\rfloor \leq \left\lfloor \frac{ \left\lfloor n \varphi + \frac{1}{b} \right\rfloor}{\varphi} + \frac{1}{b} \right\rfloor \leq \left\lfloor \frac{n \varphi + \frac{1}{b}}{\varphi} + \frac{1}{b} \right\rfloor. \end{equation} $$ With some algebra, we can simplify the terms on the left and the right some more: $$ \begin{equation} \left\lfloor n + \frac{\varphi}{b} - \frac{1}{\varphi} \right\rfloor \leq \left\lfloor \frac{ \left\lfloor n \varphi + \frac{1}{b} \right\rfloor}{\varphi} + \frac{1}{b} \right\rfloor \leq \left\lfloor n + \frac{\varphi}{b} \right\rfloor. \end{equation} $$ The upper bound on the value of the bias parameter \(b\) is the value at which the term inside the left-hand floor is infinitesimally smaller than \(n\). We can simply take \(n\) itself to be the lower limit and allow \(b\) to be the exact value for which the term reaches that limit. In short, \(\frac{\varphi}{b} \geq \frac{1}{\varphi}\). The lower bound of \(b\) is the value at which the term inside the right-hand floor function reaches \(n+1\). Now, the "\(\leq\)" has to make place for a "\(<\)" because our self-predicting property forbids the term to equal \(n+1\) exactly. By inspection, this requires that \(\frac{\varphi}{b}<1\). Taking the two bounds together, we find $$ \begin{gather} \frac{1}{\varphi} \leq \frac{\varphi}{b} < 1,\\ \varphi \geq \frac{b}{\varphi} > 1,\\ \varphi^2 \geq b > \varphi, \end{gather} $$ which specifies the range of allowed values for \(b\).

With some effort, we managed to show that for bias parameters \(\varphi < b \leq \varphi^2\), our sequence is indeed self-predicting! The sequence \(Q_n\) that specifically refers to the very next occurence of each number has to be generated by the upper bound of \(b\). After all, the sequence with this extra property always picks the smallest allowed integer for each unoccupied space, as we saw before. It then makes sense that it corresponds to the lowest bias, such that numbers are rounded down most often. Indeed, \(b = \varphi^2\) leads to the lowest bias. Finally, we obtain our sought-after formula:

\[\begin{equation} Q_n = \left\lfloor \frac{n}{\varphi} + \frac{1}{\varphi^2} \right\rfloor. \end{equation}\]Rounding off

After a rather elaborate journey along integer sequences, the golden ratio and floor functions, we managed to find a beautiful equation that describes exactly how our self-predicting sequence \(Q_n\) behaves. In a way, we found an infinite number of self-predicting sequences. Each value of the bias parameter \(b\) leads to a slightly different sequence due to the change in rounding bias.

Although the usefulness of our sequence most likely doesn’t reach beyond recreational mathematics, I found the process of exploring and uncovering its structure enlightening. A simple idea for an integer sequence unfolded into a list of progressively detailed mathematical reasoning. Much like the Fibonacci-esque chains, each new step naturally built onto the previous ones. If I had been given the sequence \(Q_n\) together with its formula, I probably wouldn’t have been particlularly impressed. However, after personally constructing and exploring the various properties of a sequence I thought up myself, reaching a final formula felt like a little discovery! This kind of drive is exactly what continues to convince me of the importance of simply giving things a go, especially in mathematics. Sometimes tackling an interesting idea leads to nothing groundbreaking, but it might as well yield an unpredicted result.

To conclude, here are the first \(100\) terms of \(Q_n\):

\[\begin{align} &0, 1, 1, 2, 2, 3, 4, 4, 5, 5, 6, 7, 7, 8, 9, 9, 10, 10, 11, 12, 12, 13, 13, 14, 15, 15, 16, 17, 17, 18, \\ &18, 19, 20, 20, 21, 22, 22, 23, 23, 24, 25, 25, 26, 26, 27, 28, 28, 29, 30, 30, 31, 31, 32, 33, \\ &33, 34, 34, 35, 36, 36, 37, 38, 38, 39, 39, 40, 41, 41, 42, 43, 43, 44, 44, 45, 46, 46, 47, 47, \\ &48, 49, 49, 50, 51, 51, 52, 52, 53, 54, 54, 55, 56, 56, 57, 57, 58, 59, 59, 60, 60, 61, \cdots \end{align}\]For more interesting integer sequences, check out the OEIS.