Bitwise operations on Braille

This post contains Unicode Braille symbols. If these are not showing, this might be due to the font used by your device.

Braille is a language that has been fascinating me for a long time. Through its elementary grid-like symbols, it enables people with visual impairments to read by touch rather than sight. Many languages have their own type of Braille, adapted to accomodate for specific letters and symbols. Besides its regular and useful functions, however, I have found Braille to be a particularly fun cipher. Though not difficult to crack (it’s simple to look up, otherwise frequency analysis will do the trick), the signs are just unrevealing enough to act as an excellent communication method between friends. They are also sufficiently simple to hide in puzzles or images. I have encountered a Braille cipher or puzzle regularly in the Dutch General Intelligence and Security Service’s (AIVD) yearly Christmas puzzle collection (Dutch), and I would say that by now I can confidently write in Unified English Braille (Grade 1, at the very least).

Yet somehow, this little language keeps finding ways to pique my interest. I want to talk about a little project of mine that started out just as a fun idea, but eventually taught me about search trees in computer science, and taught me the word “snirt”.

A language of zeros and ones

There is something about the Braille language that strongly appeals to me. The signs are extremely simple; they only have six dots, each of which can be either raised or not. This binary feature of Braille is what allows us to assign a unique sign to every letter of the alphabet, with plenty of configurations to spare. In particular, there are \(2^6=64\) combinations and only \(26\) letters. Depending on the type of Braille, the rest of the symbols are used for special characters, groups of letters, abbreviatons and more.

However, aside from their simple binary nature, the signs in Braille are far from trivial. Rather than making use of binary counting, the letters A through J have their own little configurations in the top four dots. The rest of the letters in the alphabet are constructed by repeating the ten signs with successively one and two dots filled in on the bottom row. These repetitions are called decades. An interesting exception is the letter \(\text{W}\) (⠺), which has a sign from the fourth decade assigned to it.

It struck me that each dot in a Braille sign is essentially just a \(1\) (raised) or a \(0\) (not raised). This means we can compare letters “bitwise”: we look at two Braille signs, but only compare them one dot at a time. There are a couple of operations we can consider to compare two dots:

- AND (∧): The output is a \(1\) if and only if both input dots are a \(1\);

- OR (∨): The output is a \(1\) if at least one of the input dots is a \(1\);

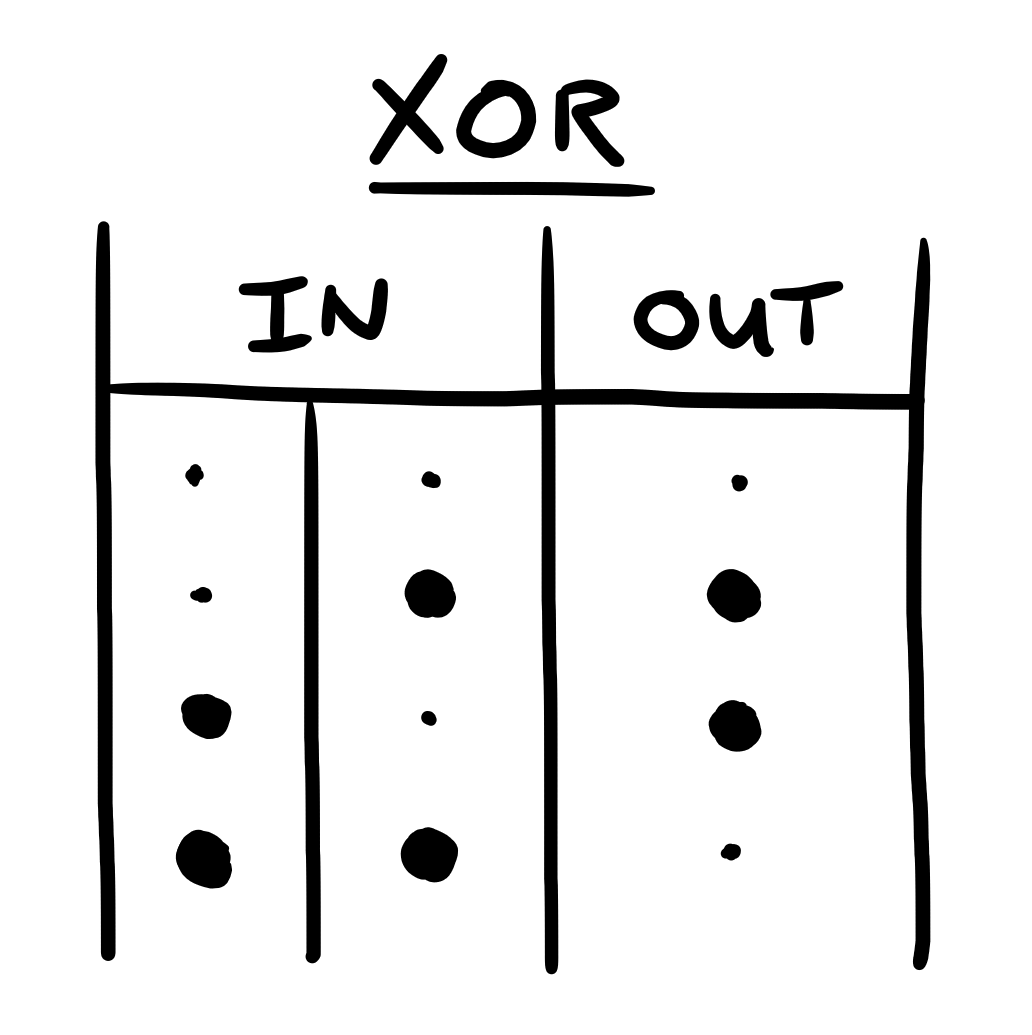

- XOR (⊻): The output is a \(1\) if and only if exactly one of the input dots is a \(1\).

Each of these binary operations has an associated negated operation (NAND, NOR, XNOR). If we perform binary operations between two letters, can we get another letter out of it?

For our purposes, an OR comparison is maybe not that interesting, since it will result in a sign with at least as many dots as the input letters. Most of the signs in Braille contain three or four dots, so we want to avoid an abundance of dots in our results. Similarly, applying an AND operation to a pair of letters will always result in a sign with an equal or lower amount of dots. These two operations could also easily give an output that is exactly the same as either of the inputs. A more interesting candidate is the XOR operation: not only might we end up with completely different signs depending on the exact arrangements of dots within the input letters, it is impossible for an output letter to be identical to one of the inputs! After all, this could only happen if one of the input letters was completely blank.

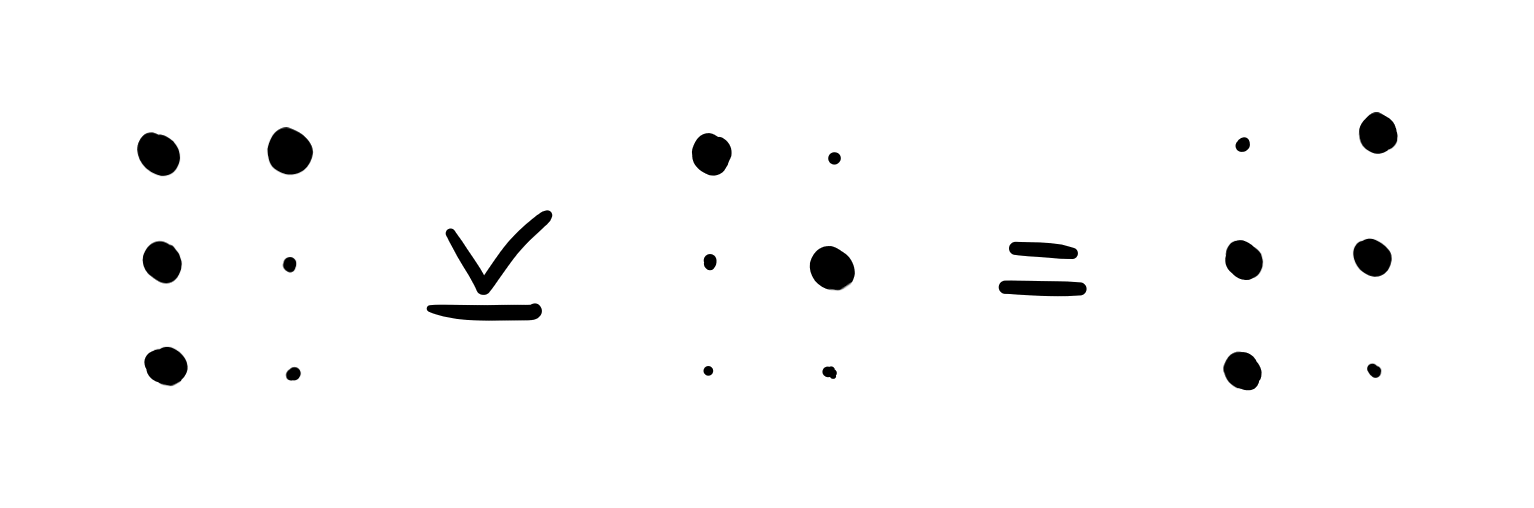

Let’s play around with this idea. Take for example the letter \(\text{P}\) (⠏). We can make another letter by XORing this with the letter \(\text{E}\) (⠑). This essentially cancels the top-left dot and adds the middle-right one, forming the letter \(\text{T}\) (⠞). The letters \(\text{E}\), \(\text{P}\) and \(\text{T}\) therefore form what I call a triplet. In fact, the order of these three letters doesn’t matter: applying the XOR operation between \(\text{T}\) and \(\text{E}\) returns \(\text{P}\) again.

Check for yourself that this is true! Does this property hold for every triplet? And does it hold for each binary operation?

The existence of these seemingly arbitrary triplets did not feel obvious at all when I was playing around with these operations, but it did raise some questions:

- Can we XOR two words in Braille to make a third word?

- If so, what is the greatest word length for which we can find a triplet?

The hunt for XOR triplets

Admittedly, there are multiple versions of Braille we could use to answer these questions. In English, the most widely used type of Braille is Unified English Braille (UEB) Grade 2, which contains many signs for abbreviations and groups of letters. For example, the \(\text{ST}\) is written as ⠌ and \(\text{AND}\) as ⠯. With \(\text{WITH}\) written like ⠾, the word \(\text{WITHSTAND}\) is neatly reduced to the three signs ⠾⠌⠯. You can imagine that this makes the goal of comparing words bitwise very tricky, since it first requires us to exactly figure out how a word is spelled using the contractions. Instead, I decided to stick with Grade 1 UEB, which simply substitutes each letter of a word with its corresponding single-letter sign. Although it reduces the amount of potential triplets, this version was more likely to withstand (⠺⠊⠞⠓⠎⠞⠁⠝⠙) my search.

The table below shows all XOR combinations of two letters in Grade 1 UEB. As expected, it is perfectly symmetric, because the order of the inputs does not matter. In fact, there is a certain sixfold symmetry due to the triplet property shown earlier, but of course this is difficult to showcase in a table. It is notable that the \(\text{I}\), \(\text{J}\), \(\text{S}\) and \(\text{T}\) form a triplet with every letter in the first and second decade. We see that \(\text{I}\) and \(\text{J}\) connect letters within the two decades, while \(\text{S}\) and \(\text{T}\) connect letters from the first decade to the second. This makes sense, given that these pairs of letters are equal aside from a raised bottom left dot. Interestingly, there are no other letters that connect the first two decades to one another. We also see several letters scattered on the bottom and on the right; upon closer inspection, this appears to be entirely caused by the irregular structure of the \(\text{W}\). All letters from the third decade are connected to \(\text{W}\) by some letter from the second decade. Lastly, note that the vowels \(\text{A}\), \(\text{E}\) and \(\text{O}\) all form a triplet with \(\text{I}\) (as mentioned before), but not with any other vowels. This will become important soon.

The next step is to compare every word in the English dictionary with every other word in the English dictionary to check if the result happens to be a word in the English dictionary. Right, that’s going to take a while. Since we want to compare the words letter by letter, we can restrict ourselves to words of equal length. However, this restriction is of little use; there are over \(32400\) words of nine letters, so the method described above would take at the very least \(32400^3 \approx 34000000000000\) operations, multiplied by nine for the word length. Indeed, my poor laptop could not handle anything beyond four-letter words when I implemented this brute-force search in Python. It is clearly necessary to construct a way to compare words faster, for example by eliminating pairs of words that contain letters that do not form triplets. But how can we do this without comparing the words in their entirety?

Trying tries

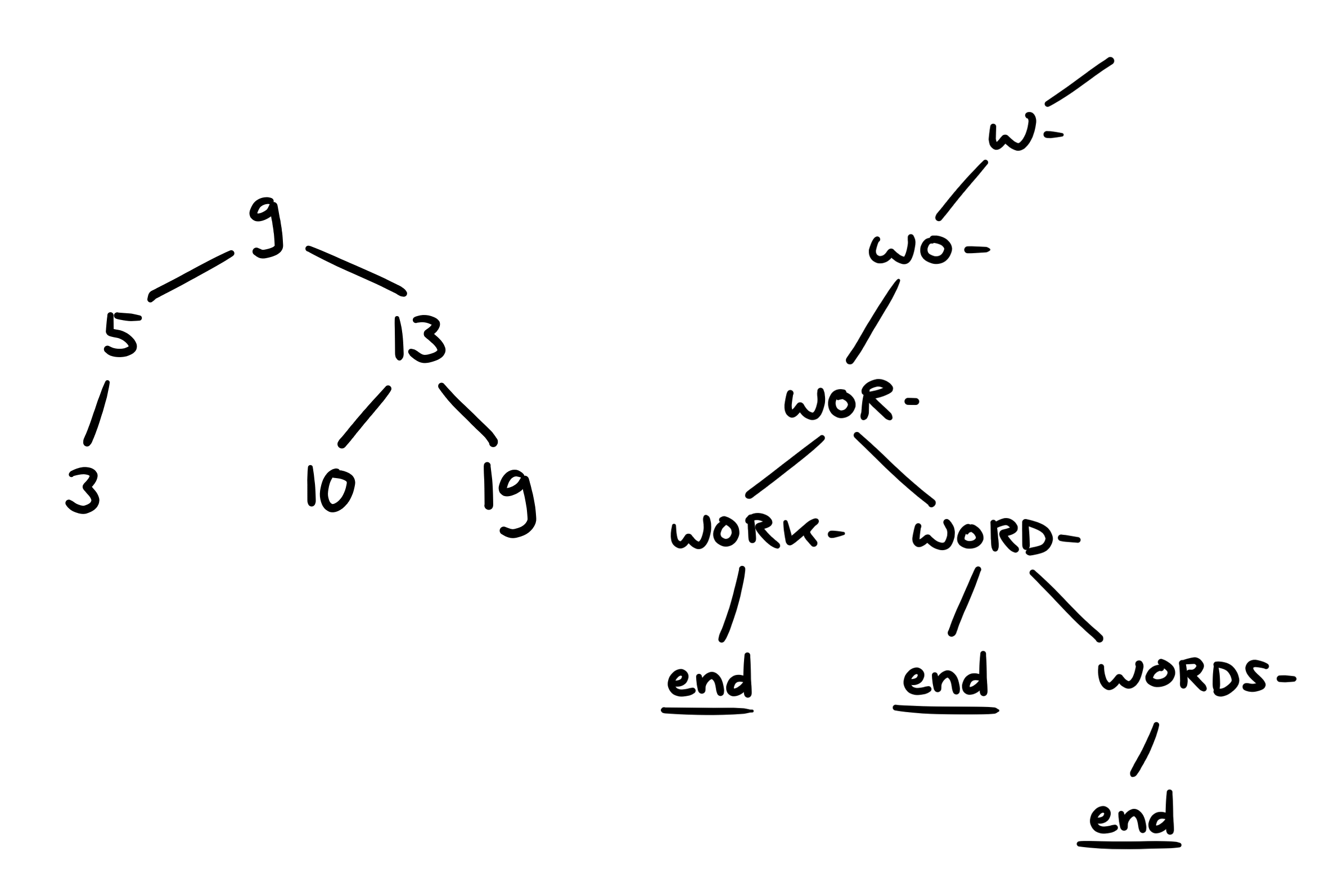

Thanks to a friend of mine, I stumbled upon the concept of search trees in computer science. Search trees are structures that are used to store and retrieve information efficiently. The trees start with a root node on top and branch off by certain rules. For example, a set of numbers (\(3\), \(5\), \(9\), \(10\), \(13\), \(19\)) could be turned into a search tree as follows: our rule will be that each node contains up to two branches, such that smaller numbers are always placed to the left and larger numbers to the right. This rule forms a so-called binary tree. We could pick \(9\) as a root and branch off to \(5\) on the left side and \(13\) on the right side. The tree structure that follows then looks like the one on the left in the image below. If each number is associated with some information, then the location of this information is easily retrievable by comparing the number with the nodes. It now only takes up to three comparisons to reach the location of any number, rather than up to six if we were to compare against each element in the set.

Another type of search tree is a prefix tree, also called a trie. A trie splits words into prefixes, which construct words as we traverse down the trie. For example, the words WORD and WORK have a common prefix WOR-, so they trace they same path down the trie (W-, WO-, WOR-) until they finally split off into separate branches. It is then possible to add an “end” node, which indicates that a valid word has been reached. The prefix WORD- can then split off into WORD (end) and WORDS-, which continues the trie. This is shown on the right side in the image below. Since we already split the dictionary into words of equal length in advance, we will not bother with end nodes but simply go down the entire tree.

Tries provide the perfect solution to our problem: they allow us to perform all three searches through the dictionary at once. First, we construct a trie containing all words in the English dictionary of a certain length. We use an empty string for the root node, which branches out into \(26\) leaves A- to Z-. The strategy is as follows:

- Traverse each branch down to the very bottom, to form word 1;

- For each word 1, loop through the branches of the root node to start constructing word 2;

- Check whether XORing the first letter of word 1 with the first letter of word 2 gives a valid letter as output;

- If the output is valid, save the output branch to construct word 3 and loop over the branches of the first letter of word 2 to pick a second letter;

- Check whether XORing the second letter of word 1 with the second letter of word 2 gives a letter that exists as a branch of the first letter of word 3;

- If it is, then repeat the above two steps and dive deeper into word 2 and word 3. If it is not, then stop the process and find the next word 1.

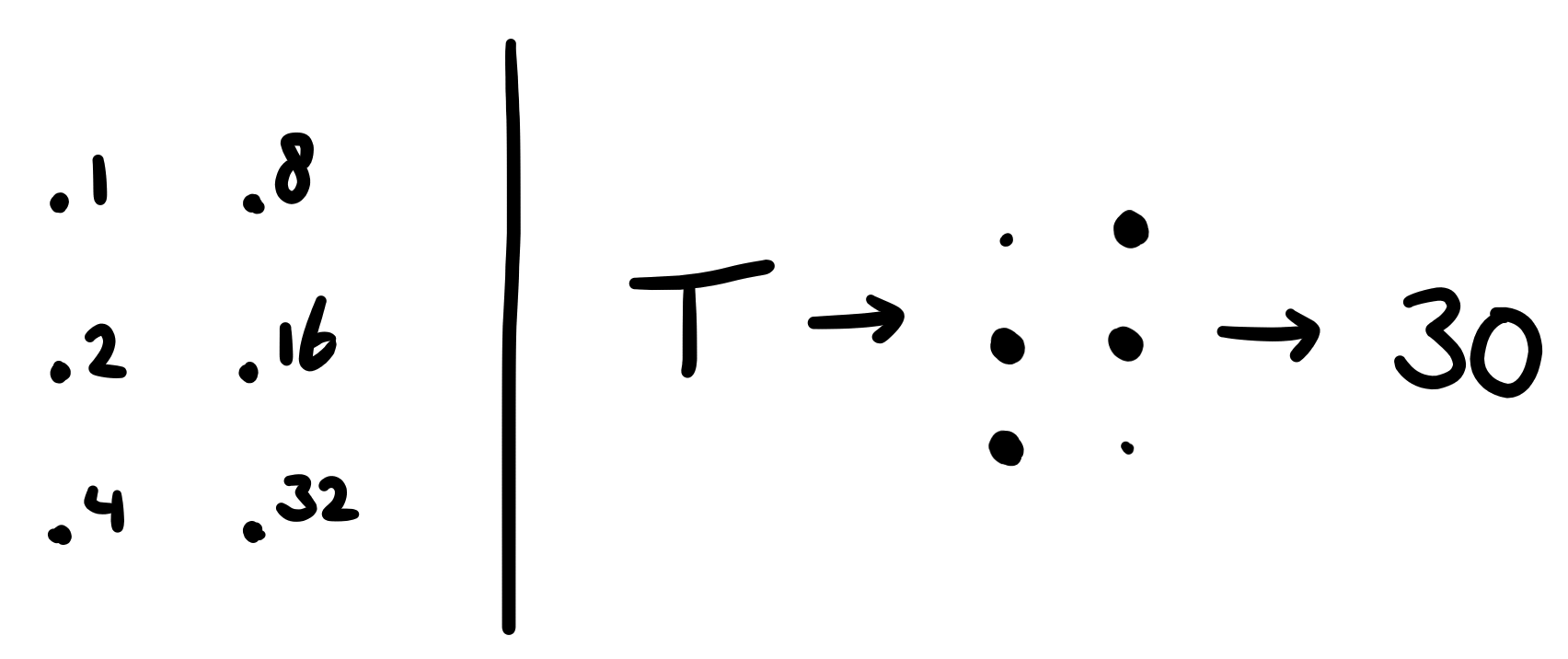

I implemented this method in Python, making use of the nltk.corpus.words dictionary from the nltk library. Since words with hyphens were a tricky case, I removed these from my analysis completely. The code only took around four seconds to run for nine-letter words; all other word lengths took less time to search through! To XOR the letters in Braille, I used somewhat of a shortcut: instead of comparing each dots separately, I considered the Braille signs as six digit binary numbers. The trie contained these numbers as nodes (in decimal, for simplicity), which made it incredibly easy to XOR the letters and to check whether the output letter existed as a branch for word 3.

Results

The answer is convincing: yes! We can absolutely XOR two words in Braille and get a valid word out. For two, three and four-letter words, there was a surprising amount of triplets. My code gave \(31\), \(192\) and \(96\) hits, respectively. Of course, many of these words are vague or uncommon, but some of them are certainly worth appreciating. Let’s look at a few noteworthy triplets.

Three letters

For three letters, I quite liked these triplets:

$$\text{AGE} \; \veebar \; \text{PET} \; = \; \text{SIP}$$ $$\text{ALE} \; \veebar \; \text{FIT} \; = \; \text{IMP}$$ $$\text{ART} \; \veebar \; \text{FIB} \; = \; \text{INN}$$ $$\text{EGG} \; \veebar \; \text{PSI} \; = \; \text{TOE}$$

Four letters

For four letters, I had a laugh at this rather inappropriate triplet:

$$\text{ARSE} \; \veebar \; \text{PIPI} \; = \; \text{SNAG}$$

And what about something a little more international?

$$\text{ANGO} \; \veebar \; \text{FIJI} \; = \; \text{IRAQ}$$

Or this lizard falling off a tropical tree:

$$\text{DROP} \; \veebar \; \text{HISS} \; = \; \text{INGA}$$

Five letters

Five-letter triplets turned out particularly interesting: I found a total of five five-letter triplets. Here is the complete list:

$$\text{ADROP} \; \veebar \; \text{PINTE} \; = \; \text{SHIFT}$$ $$\text{APHIS} \; \veebar \; \text{PEDRO} \; = \; \text{STING}$$ $$\text{ARGIL} \; \veebar \; \text{PIEND} \; = \; \text{SNIRT}$$ $$\text{BIFID} \; \veebar \; \text{CRAFT} \; = \; \text{INIAL}$$ $$\text{ENROL} \; \veebar \; \text{PRISM} \; = \; \text{TINGI}$$

It is interesting that the vast majority of triplets contain an \(\text{I}\), but it makes sense: \(\text{I}\) and \(\text{J}\) form the most triplets with other letters, and \(\text{I}\) is the only vowel that forms a triplet with the vowels \(\text{A}\), \(\text{E}\) and \(\text{O}\). Since each (proper) word requires some vowel, it is inevitable that the \(\text{I}\) shows up in at least one of the words.

Here are the definitions of the words, according to the Merriam-Webster dictionary:

- \( \text{ADROP:} \) A substance (as lead) believed essential to evolving the philosophers’ stone.

- \( \text{APHIS:} \) Any of a genus (Aphis) of aphids.

- Aphid: Any of numerous very small soft-bodied homopterous insects (superfamily Aphidoidea) that suck the juices of plants.

- \( \text{ARGIL:} \) Clay, especially potter’s clay.

- \( \text{BIFID:} \) Divided into two equal lobes or parts by a median cleft.

- \( \text{CRAFT:} \) An occupation, trade, or activity requiring manual dexterity or artistic skill. [and more definitions]

- \( \text{ENROL:} \) To insert, register, or enter in a list, catalog, or roll.

- \( \text{INIAL:} \) [From Wiktionary] Relating to the inion.

- Inion: A small protuberance on the external surface of the back of the skull near the neck; the external occipital protuberance.

- \( \text{PEDRO:} \) Dom; name of two emperors of Brazil.

- \( \text{PIEND:} \) Arris.

- Arris: The sharp edge or salient angle formed by the meeting of two surfaces, especially in moldings.

- \( \text{PINTE:} \) [From Wiktionary] A French-Canadian term for an Imperial quart, equal to \( 1/4 \) of an Imperial gallon, \(2\) Imperial pints, \(40\) Imperial ounces or \(1.136\) liters.

- \( \text{PRISM:} \) A polyhedron with two polygonal faces lying in parallel planes and with the other faces parallelograms. [and more definitions]

- \( \text{SHIFT:} \) To change the place, position, or direction of. [and more definitions]

- \( \text{SNIRT:} \) (Chiefly Scottish) An unsuccessfully suppressed snort of laughter.

- I found this one particularly funny.

- \( \text{STING:} \) To prick painfully. [and more definitions]

- \( \text{TINGI:} \) [From Wiktionary] A Brazilian tree, Magonia pubescens, whose seeds yield soap.

And with that, I can also answer the second question: there are no triplets with words longer than five letters. The maximum word length is therefore five, and all the triplets for this length are given above.

Dotting the \(\text{I}\)'s

The patterns in Braille have surprisingly complex and fun properties. By interpreting this intriguing little language of dots as binary numbers, we can perform binary operations on each dot separately and combine two words to form one that is entirely different. When I thought of this little idea, I had no idea that it would teach me about search trees, or that the result would be so satisfying. All because of what I now consider the best letter in Braille: the \(\text{I}\) (⠊). Without it, there would not have been a single (proper) triplet of words. Of course, our final result is of little direct importance, even if it makes a good fun fact to tell at room parties. However, the triplet search itself was definitely worth the patience. Perhaps sometime in the future, I’ll come back to this little project to include groupsigns in the analysis. I can’t yet tell whether I will find more triplets in Grade 2 Braille, but at the very least they exist in Grade 1. Doesn’t that feel like a sign?

⠞⠓⠁⠝⠅⠎⠀⠋⠕⠗⠀⠗⠑⠁⠙⠊⠝⠛ !